Also known as giant cell and cranial arteritis, temporal arteritis is a systemic vasculitis of medium-sized and large-sized arteries. Temporal arteritis is the most common systemic vasculitis of older adults. Symptoms of temporal arteritis can be constitutional or vascular related. Constitutional symptoms include fever, weight loss, anemia, and fatigue. Vascular-related symptoms arise secondary to arterial inflammation with luminal stenosis and resultant end-organ ischemia. Temporal artery biopsy is the criterion standard to establish the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. A positive histologic diagnosis demonstrates inflammation of the arterial wall with fragmentation and disruption of the internal elastic lamina. Multinucleated giant cells are found in less than half of the cases and are not specific for the disease. The 3 histological patterns of temporal arteritis include the classical, atypical, and healed. The disease typically responds well to rapid administration of systemic corticosteroids, regardless of histological subtype. The incidence rate for temporal arteritis is 15-25 cases per 100,000 persons over the age of 50,1 with a mean age at presentation of 71 years old.2 Temporal arteritis is the most common systemic vasculitis of adults in Western countries. Women are affected at least twice as often as men.1 Disease susceptibility is associated with northern European decent and is seldom observed in blacks and Asians.2,3 The cause of temporal arteritis is multifactorial and is determined by both environmental and genetic factors. Emerging data have shown that the disease is likely initiated by the exposure to an exogenous antigen. Numerous viruses and bacteria have been proposed as potential precipitants. These include parvovirus, parainfluenza, varicella zoster, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Temporal arteritis shows a predilection for the vertebral arteries, the subclavian arteries, and the extracranial branches of the carotid arteries (superficial temporal, ophthalmic, occipital, and posterior ciliary arteries). Temporal arteritis and giant cell aortitis are related, and the inflammation may involve the aortic wall and, rarely, the femoral and coronary arteries. The onset of symptoms in temporal arteritis may be gradual or sudden. Arterial wall infiltration by lymphocytes and macrophages leads to luminal stenosis and occlusion of the vessel. Consequently, many of the clinical symptoms are a reflection of end-organ ischemia. The branches of the internal and external carotid arteries are particularly at risk. Their involvement produces the classic clinical manifestations of jaw claudication, headache, scalp tenderness, and visual disturbances. A systemic inflammatory response frequently accompanies the vascular manifestations of temporal arteritis and produces a constellation of symptoms. Fever, myalgia, anorexia, weight loss, anemia, and malaise are often encountered. Acute phase reactants such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein are typically elevated. Polymyalgia rheumatic (PMR) is characterized by stiffness and pain of the proximal joints. It occurs in 50-75% of patients with temporal arteritis.1,5 Vision loss is not a feature of PMR. PMR may progress into clinical temporal arteritis and is considered by some to represent a different phase of the same disease. The differential diagnoses for a patient presenting only with the systemic inflammatory symptoms of temporal arteritis is broad. Systemic infections, connective tissue diseases, and malignancies may share similar clinical features. Primary systemic amyloidosis can mimic the symptoms of both PMR and temporal arteritis. Patients with a monoclonal band on immuno-electrophoresis and a poor response to systemic corticosteroids should have a Congo red stain performed on a temporal artery biopsy. The ophthalmic features of temporal arteritis can be mimicked by nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), a disease characterized by visual disturbances in patients with cardiovascular risk factors and a susceptible ”crowded” optic disc. Several features can be used to differentiate NAION from temporal arteritis. NAION typically occurs in a younger age group with a mean age of 60. Constitutional symptoms are absent in NAION and erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are within normal limits. The visual changes in NAION are less severe and typically do not result in complete vision loss. On ophthalmic examination, the cup/disc ratio is reduced in NAION (”crowded”) but is normal in temporal arteritis.8 Several vasculitides and connective tissue disorders can present with similar systemic and ophthalmic manifestations and include systemic lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosa, Churg Strauss, microscopic polyangiitis, Takayasu arteritis, and polymyositis. Differences in systemic organ involvement, microscopic findings, and distribution of lesions can help to distinguish these entities from temporal arteritis. Compressive intracranial lesions, both malignant and benign, can also be considered in the differential but can be ruled out with neuroimaging studies. No consensus agreement exists regarding the optimal dosage and duration of corticosteroid administration. Corticosteroids act to suppress the inflammatory response in temporal arteritis and limit the ischemic complications of the disease. It is universally agreed that treatment should be initiated as soon as the diagnosis is suspected and that steroids should be given even before the biopsy is obtained. Segments of affected arteries develop nodular thickenings that produce stenosis of the lumen. The lesions may be associated with thrombi, which occasionally organize and transform the artery into a thick fibrous cord. Aortic involvement by giant cell aortitis may give the luminal surface a longitudinal wrinkled look, the so-called ”tree-bark” appearance. This finding is not pathognomonic for giant cell arteritis and is found in all aortitis. This appearance is secondary to alterations occurring in the media including elastic fibre fragmentation, loss of medial smooth muscle, and medial scarring. The most important anatomic characteristic of temporal arteritis is the segmental distribution of the inflammatory infiltrate that results in the formation of "skip lesions." "Skip lesions" have been observed in some studies to occur in as many as 28% of cases.9 As a result of the segmental nature of the inflammation, an adequate biopsy requires a length of at least 2 cm to 3 cm and the submission of multiple sections for histological analysis. The lack of diagnostic microscopic features on biopsy does not rule out the disease, and this may occur in 15% of cases.4 The second pattern is the atypical type, which may represent an intermediate stage in the resolution of the classical type. The atypical pattern is typified by a less dense nonspecific arteritis with an inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and macrophages with rare eosinophils and neutrophils. Moderate or marked intimal thickening and medial fibrosis are sometimes noted. Granulomas and multinucleated giant cells are only rarely observed. The inflammation tends to be most marked in the adventitia. Intimal fibromyxoid changes and inflammation are also found.10 The final histological pattern is the healed type, which demonstrates intimal and medial fibrosis. The intima is irregularly thickened, has fibromyxoid change and neovascularization, and fibrosis of the media may be seen. A trichrome stain may be useful to detect this. Elastic stain highlights significant defects on the internal elastic lamina. Frequently, these are over 30-50% of the circumference of the artery. Focal areas of persistent chronic inflammation remain.10 Some concern exists that treatment of temporal arteritis with corticosteroids can lead to resolution of the arterial inflammation and a decreased diagnostic accuracy of the temporal artery biopsy. However, the treatment effects appear to have minimal impact on the histological features, especially if corticosteroids have been administered less than 14 days prior to biopsy.4 Leukocyte common antigen (LCA) and CD15 can be used to identify inflammatory cells when no definite inflammation is observed on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Histiocytic markers (CD68 and HAM56) can detect residual arteritis in patients with resolving disease.11,12 Temporal arteritis appears to have a genetic predisposition, based on its familial, ethnic, and geographic distribution. Studies have shown familial clustering and monozygotic twin concordance. Most genetic factors center on the HLA genes. It is likely that various HLA alleles predispose to temporal arteritis and mediate its severity. Temporal arteritis is not a tumor; therefore, no staging system exists. Before the advent of corticosteroids, most patients afflicted with temporal arteritis lost their vision. With current adequate therapy and rapid diagnosis, the incidence of blindness has been lowered to 9-25%.2 Once vision loss has occurred, it is irreversible despite corticosteroid therapy. The mortality rates of patients with treated temporal arteritis are the same as those for healthy, age-matched individuals.13 Although most patients are symptom free after 3 years of therapy, half of them will require ongoing management with corticosteroids. Significant morbidity is associated with prolonged corticosteroid therapy, including the development of cataracts, hypertension, myopathies, and osteopenia.4 Temporal Arteritis

Definition

Temporal arteritis may also involve the aorta and may be associated with aneurysm, dissection, and aortic rupture. Typical involvement of the temporal, vertebral, and ophthalmic arteries leads to the classic clinical manifestations of headache, facial pain, and vision problems. Inflammation of the ophthalmic artery can lead to irreversible blindness of sudden onset. Vision loss in temporal arteritis is a medical emergency requiring prompt recognition.

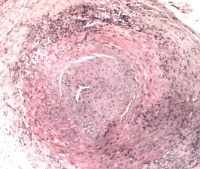

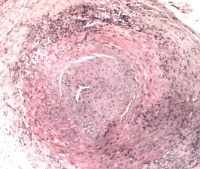

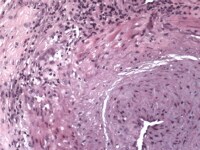

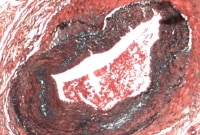

Temporal arteritis.

Epidemiology

Etiology

T lymphocytes are recruited to the vessel wall after initial exposure to the antigen. They release alpha-interferon (α-IFN) and other cytokines that act upon local macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. The response of the macrophages and multinucleated giant cells to the cytokines depends upon their location within the vessel wall. Adventitial-based macrophages produce interleukin-6 (IL-6), which further serves to augment the inflammatory cascade. Macrophages within the media produce oxygen free radicals and metalloproteases, which degrade the arterial wall and fragment the elastic lamina. With the disruption of the internal elastic lamina, the intima becomes accessible to migrating myofibroblasts, which proliferate and lay down extracellular matrix.

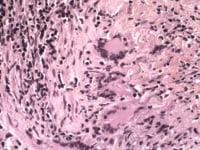

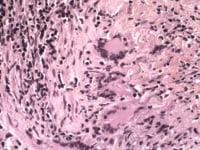

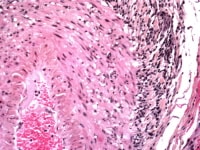

Temporal arteritis giant cells.

This migratory process is driven by intimal-based macrophages that produce platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The net effect of these events is an arteritis with local vascular destruction and intimal hyperplasia leading to luminal stenosis and occlusion. The exuberant release of cytokines associated with this process may be responsible for the constitutional symptoms that are frequently encountered with the disease.4,5,6,7Location

Clinical Features and Imaging

One of the most significant complications is complete or partial vision loss, a phenomenon that occurs in at least one eye in up to 60 % of patients.4 Blindness results from occlusion of the inflamed ophthalmic or posterior ciliary arteries with resultant ischemia of the optic nerve or tracts. Other potential visual disturbances that may precede vision loss include diplopia, amaurosis fugax, hallucinations, blurred vision, and eye pain. Inflammation of the posterior vertebral arteries can decrease the posterior cerebral perfusion and lead to dizziness, vertigo, transient ischemic attacks, and cerebrovascular accidents. Absent or asymmetric pulses and claudication of the arms can occur when the arteritis affects the axillary, subclavian, and proximal brachial arteries. Inflammation may involve the aorta with potential sequelae of thoracic aneurysms, dissections, and rupture.

Early initiation of therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of blindness and stroke. The dosing regimens of steroid administration vary, but, generally, the greater the visual loss or the potential for visual loss, the larger the dose of corticosteroids required. Individual treatment regimens are based on the clinical presentation, the severity of symptoms, the response to treatment, and the development of adverse side effects. Corticosteroid doses are gradually tapered to a minimally suppressive amount that induces clinical remission to limit the development of potential complications of prolonged corticosteroids. Various immunosuppressive agents are now being considered for their potential steroid-sparing effects. Conflicting results have been obtained and the current mainstay of treatment is still high-dose systemic corticosteroids.Gross Findings

This postprocessing cutting method is optimal because it ensures a good orientation of the vessel segments. The cross-sections should be cut in serial sections onto slides. Interval staining of slides is performed. If negative, the tissue should be completely sectioned and depleted so as not to miss a focal involvement, as will be discussed.Microscopic Findings

Three patterns of vascular damage are frequently seen in temporal arteritis. The first pattern is the classical type characterized by marked intimal thickening and transmural inflammation. A dense inflammatory infiltrate composed of T lymphocytes and histiocytes is present. Fusion of histiocytes results in the classic microscopic appearance of granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (foreign body and Langhans types). This finding is found in less than 50% of cases and is not specific to temporal arteritis. Release of inflammatory mediators causes fragmentation and distortion of the internal elastic lamina. An elastic stain is essential in the evaluation of these biopsy specimens. The intima often has a fibromyxoid appearance.4,10 Immunohistochemistry

Molecular/Genetics

Individuals homozygous for human leukocyte antigen DR4 and the FCGR2A-131RR allele have a 6-fold increased risk in developing temporal arteritis. HLA-DR1, HLA-DR3, and HLA-DR5 may also be associated with a higher incidence of the disease. Polymorphisms in immunomodulating proteins such as interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 have also demonstrated an increased association with temporal arteritis. The precise role of genetic susceptibility in temporal arteritis remains unclear and requires further investigation.8,2,4,7Tumor Spread and Staging

Prognosis and Predictive Factors

Multimedia

Media file 1: Temporal arteritis.

Media file 2: Temporal arteritis giant cells.

Media file 3: Temporal arteritis giant cells.

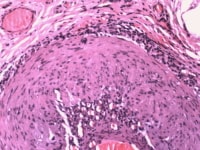

Media file 4: Temporal arteritis atypical features; adventitial heavy inflammation.

Media file 5: Temporal arteritis adventitia and intimal inflammation predominate; atypical features.

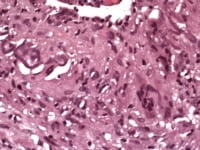

Media file 6: Temporal arteritis fragmented internal elastic lamina.

Media file 7: Temporal arteritis large gap in the internal elastic lamina; this is best seen with an elastic stain (Movat pentachrome, in this example).

Sunday, October 17, 2010

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

Labels: Temporal Arteritis

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment