A "medical device" can be defined as any physical item useful for diagnostic, monitoring, or therapeutic purposes. Numerous types of medical devices are available, ranging from relatively simple external objects, such as adhesive bandages, examination gloves, and wheelchairs, to high-tech implanted internal devices, such as cardiac pacemakers and cochlear implants. Although this chapter mentions nonimplanted devices, it will primarily focus on implanted medical devices (IMDs) encountered at autopsy. The image below depicts several medical devices. With the rapid progress that has been made within the medical sciences over the past century, thousands of diagnostic and therapeutic devices have been developed. Because these devices are used on patients, with at least a theoretical potential for misuse or harmful side effects, a system of government-operated oversight and regulation exists. Within the United States, medical devices are primarily regulated via the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). For an object to be under such regulation, the device must first meet the criteria established by the FDA to be designated as a medical device.1The official FDA criteria are furthered defined in the Definitions section. Although finding specific numbers within the medical literature is difficult, there is no doubt that the number of patients with implantable medical devices has increased markedly over the past several decades. A 2004 study estimated that in the years 1997 and 2000, over 500,000 implanted medical devices were placed in pediatric patients.2 Medical devices are as varied as the medical conditions for which they are designed. The FDA recognizes hundreds of different medical devices. They are divided into 3 different general classes, based on their potential for harm and degree of "invasiveness." These classes are further defined in the Definitions section below.3 Because more than 1700 medical devices are recognized by the FDA, providing information regarding the indications for use for each of them is well beyond the scope of this article. The reader should recognize that, in general, the devices may be considered diagnostic, monitoring, therapeutic, prosthetic, or surgical in nature. For each, guidelines and recommendations exist for appropriate usage. Physicians and/or other healthcare providers, usually in cooperation with an informed and consenting patient, determine if and when the implementation of the device is warranted. The following is the official FDA definition of a medical device, as defined by the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C), United States Code 201(h): The definition allows for a distinction between medical devices and other FDA-regulated substances, such as drugs. If an object meets the definition above, the device is subject to premarket and postmarket FDA regulation. The image below depicts an anesthesiology device. The images below depict cardiovascular devices. The image below depicts a gastroenterology device. Some neurology devices are depicted in the images below. The image below depicts an orthopedic device. The scene examination in cases involving persons with implanted medical devices varies greatly. In virtually all cases, the scene examination is similar to many other forensic scene investigations, in which investigators should first evaluate the scene for potential safety hazards for investigators, first responders, and bystanders. Issues of concern include, but are not limited to, electrocution, water or other fluids, explosion hazards, and fire hazards. Depending on the medical device involved in a given case, electrical hazards may be a very legitimate concern. Whether or not trace evidence exists in cases of death related to implanted medical devices depends entirely on the type of device present. In many cases, such trace evidence is lacking. In certain case types, however, valuable trace evidence may be present at the scene, on the body, or in the body. Items such as residual medication contained within a used syringe or air-bubbles within IV tubing may be vitally important in certain cases. Soft tissues underlying the site of a skin injection site may represent a valuable piece of evidence in certain cases. When an autopsy is to be performed on a person who has an implanted medical device, the pathologist should aware of several important issues and facts. Air embolism In this section, the authors provide a few comments for certain FDA device panels. Only select panels are discussed, as several panels have a very low likelihood of being associated with death. An image depicting a knee replacement prosthesis can be seen below. Certain types of implanted medical devices require specialized handling. With some devices, careful handling is essential in order to ensure the safety of pathologists, autopsy assistants, and funeral home personnel. Any device containing sharp points or edges has the potential to cause puncture wounds, with the associated risks of blood/body fluid contamination. Items such as needles, metal wires, clips, orthopedic screws, vena cava "umbrellas," and intravascular metallic stents (see the images below) all have the capacity to cause puncture wounds. Whether or not microscopy might be important in a death related to an implanted medical device depends on the device type, as well as the suspected mechanism of death. For example, if an implanted device is contaminated with bacteria and results in a localized infection with subsequent abscess formation, histologic documentation of the abscess is in order. Another example might involve a situation in which localized inflammation with associated tissue breakdown and hemorrhage occurs at the site of an implanted device. In such a case, histologic sections help to document the process. Photography is an important method of documenting autopsy findings. When an implanted medical device is suspected by family members (or attorneys, or anyone else) of having caused or contributed to death, taking photographs of the device in situ is a wise practice, whether or not the device contributed to death. In many cases in which the device is suspected to have caused or contributed to death, autopsy proves that the device had nothing to do with death. As such, documenting this "negative finding" by photography can help to avoid countless hours of debate with someone unwilling to accept the autopsy findings. This article has mentioned that for certain implanted medical devices, typically those that are electronic, the devices can be electronically interrogated in order to provide useful information. The most common example of this involves implanted cardiac defibrillators, although other devices can also be interrogated. Oftentimes, the manufacturer representatives can assist with this interrogation. Cause and manner of death determination are important components of a forensic/medicolegal death investigation. Obviously, many nonforensic, hospital pathologists who perform autopsies are well acquainted with these issues, especially the cause of death; however, some are not. Hospital pathologists must be especially aware of manner-of-death issues, as some cases related to implanted medical devices might require notification of the local medicolegal death investigation office (coroner or medical examiner). Although the above classification scheme can be helpful in dealing with these difficult death investigations, it does not change the fact that they remain difficult death investigations. Placing a particular death into one of the 5 categories can sometimes be very challenging. From the general public's point of view, 2 misconceptions exist with regard to implanted medical devices. The first is that it is highly likely that death was related to an implanted medical device when a person with such a device dies. In fact, the exact opposite is the truth. In a vast majority of deaths involving persons who have implanted medical devices, the devices have absolutely nothing to do with death. Even if death occurs at or near the time of device implantation, it is relatively rare for the device or implantation procedure to cause or contribute to death. Device-related and procedural-related deaths absolutely do occur, but they are the exception, rather than the rule. When a medical device is found to have caused or contributed to death, the most likely court-related issues relate to civil court, rather than criminal court. If a device is truly defective, and the device is found to have resulted in the death of a patient, the case will likely end up in civil court. Depending on the extent of device use and the number of deaths that result from it, class-action lawsuits may occur.Implanted Medical Devices

Introduction

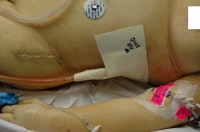

This autopsy photo shows several medical devices, many of which are combination internal/external devices, including an arterial line, an intravenous line, and a chest tube. Also note the recent surgical scar, containing implanted (totally internal) sutures, as well as the electrocardiograph (ECG) pad, a totally external device.

History

The mere presence of an implanted (or external) medical device within a dead body does not mean that it played a role in death. In fact, in most cases in which a device is identified at autopsy, the device does not play a role in death. However, in rare circumstances, a medical device is found to cause or contribute to death. In such cases, the device may or may not have been working appropriately. In some cases, the device was used improperly. When confronted with an autopsy case in which a medical device is suspected of causing or contributing to death, pathologists should take great care to document all findings and, if possible, remove and retain the device. A more detailed list of recommended guidelines for autopsy pathologists occurs later in this chapter.Epidemiology

Overview of the Entity

In a separate classification scheme, the FDA divides the devices into 16 different categories based on the type of medical condition for which they are used. More than 1700 medical devices are classified into 16 different FDA medical "panels" (or specialties), which include anesthesiology; cardiovascular; clinical chemistry and clinical toxicology; dental; ear, nose, and throat; gastroenterology and urology; general and plastic surgery; general hospital and personal use; hematology and pathology; immunology and microbiology; neurology; obstetric and gynecologic; ophthalmic; orthopedic; physical medicine; and radiology.4

Medical devices can further be classified based on whether or not they are implanted within the body. Devices can be 1) totally external, 2) totally internal, or 3) combined external and internal (see the following image).

This autopsy photo shows several medical devices, many of which are combination internal/external devices, including an arterial line, an intravenous line, and a chest tube. Also note the recent surgical scar, containing implanted (totally internal) sutures, as well as the electrocardiograph (ECG) pad, a totally external device.

This chapter focuses specifically on implanted medical devices and how their examination and evaluation may be an important aspect of an autopsy/death investigation. However, the examination and evaluation of nonimplanted (totally external) medical devices and combined external/internal devices may be important in other cases. Some of the same recommendations regarding the evaluation of implanted medical devices may be applied to these other devices.

When approaching a case in which an implanted medical device is suspected to have caused or contributed to death, pathologists must gather information about the device before autopsy, determine if any safety hazards are associated with the device, perform a detailed and complete autopsy examination, document all findings, and be unbiased. Contacting hospital risk management personnel, nursing services personnel, and the attending physician before autopsy if the patient died as a hospital inpatient may be appropriate.5

If the death occurred during the performance of a procedure, the pathologist must understand that procedure before performing the autopsy. Discussing the case with the persons involved may or may not always be practical but should occur, if possible. Pathologists should obtain copies of medical records as soon as possible in such cases. Hospital staff should be educated to leave all medical therapy and devices in place and undisturbed after a death has been pronounced.5Indications for the Procedure

For pathologists performing an autopsy on a patient who has an implanted medical device, it is recommended that, before autopsy, the pathologist learn as much as possible about the device, its indications for use, its function, the disease or condition for which it is employed, when it was implanted, and any potential complications or safety risks known to occur with the device. Depending on the device, this may require consultation with physicians within various medical specialties.

In the next section, an attempt will be made to provide a more detailed review of the 16 FDA categories, with examples of the types of medical devices within each category.Definitions

"A device is: an instrument, apparatus, implement, machine, contrivance, implant, in vitro reagent, or other similar or related article, including a component part, or accessory which is:

Similar definitions exist in other countries. A more simple definition is: "an object that is useful for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes." As mentioned in the Introduction, medical devices may be rather simple or quite complex. Some are used externally. Some are used internally. Others have parts that are external and parts that are internal. Many are electronic, but many are not. The FDA has 3 different classes of medical devices.

Class I medical devices

In general, class I devices have a minimal potential risk of causing harm and are subject to general control measures, such as good manufacturing techniques and proper labeling. Examples include tongue depressors, gloves, bedpans, and handheld surgical instruments.

Class II medical devices

Class II devices have a higher potential to cause harm and require both general and special controls, such as special labeling, mandatory performance standards, and postmarket surveillance. These devices are typically nonimplanted, although some are partially invasive. Examples include x-ray machines, wheelchairs, infusion pumps, and surgical needles.

Class III medical devices

Class III devices pose a much more significant potential risk, often because they are more invasive. These devices require general controls and premarket approval (scientific review to ensure the device's safety and effectiveness). Examples of class 3 devices include heart valves, orthopedic prosthetic devices, and cardiac pacemakers.3

Although class I devices may be considered less potentially harmful than class II devices, which may be considered less potentially harmful than class III devices, concluding that "simple" devices cannot cause serious injury or death is wrong. Examples of deaths related to devices within all 3 classes are abundant.

Besides the overall safety/risk classification (classes I-III), every medical device that is approved by the FDA has been classified based on the medical "panel" (specialty) to which it belongs (eg, anesthesia vs orthopedic vs cardiac). Sixteen medical panels exist (see below).

By searching the FDA's website, interested persons can learn the exact FDA identification and classification for a particular medical device. Devices are classified based on the medical specialty ("panel") to which they belong; the subcategory of device type (diagnostic, monitoring, therapeutic, prosthetic, surgical, or miscellaneous); and whether they represent class I, II, or III devices. The site provides a general description of the device, as well as production regulations.4

In the remainder of this section, each of the 16 medical specialty areas ("panels") as defined by the FDA will be examined. Some general comments will be made for each. For some of the 16 (those that have medical devices that have a realistic risk of death), additional commentary will be provided, with specific regard to autopsy/death investigation. An attempt will be made to provide specific examples regarding medical devices within each category. It is well beyond the scope of this treatise to examine every single implanted medical device. For perspective, consider the following example. Within the anesthesiology panel, over 140 specific medical devices exist, many of which are implantable. Considering each device in this article would be impossible.

I - Anesthesiology devices

Included here are a variety of external and internal medical devices utilized in the medical specialty of anesthesiology. Most of the devices are external or combination internal/external. Most deal specifically with airway management, although some involve vascular access. Other vascular access devices are included under the cardiovascular category.

Most anesthesiology devices are class I or class II devices. Examples of class I devices include oropharyngeal airways (endotracheal tubes), arterial blood gas sampling kits, esophageal stethoscopes, and tracheobronchial suction catheters. Examples of class II devices include carbon dioxide gas analyzers, indwelling blood oxygen partial pressure analyzers, apnea monitors, and ventilators. An example of a class III device is a membrane lung for long-term pulmonary support (extracorporeal blood oxygenation).

An autopsy photograph showing multiple medical devices, including a tracheostomy tube, which would be classified as an anesthesiology device.

II - Cardiovascular devices

Numerous invasive and noninvasive medical devices are included within this category. Included here are devices specifically involving the heart, as well as many that involve blood vessels. As with many other medical panels, the cardiovascular devices include diagnostic devices, monitoring devices, prosthetic devices, surgical devices, and therapeutic devices, among others.

Class I cardiovascular devices include items such as traditional stethoscopes and specialized cardiothoracic surgery instruments (eg, forceps, scissors). Examples of class II devices include percutaneous catheters, blood pressure cuffs, vascular graft prostheses, catheter guidewires, and vascular clamps. Class III cardiovascular devices include items such as implantable pacemakers, implantable defibrillators, prosthetic heart valves, ventricular bypass (assist) devices, and intraaortic balloon pumps.

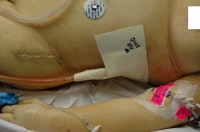

Implanted vascular graft material used to replace an area of ascending aortic aneurysm and dissection.

A coronary artery stent as visualized at autopsy.

A photograph of a Swan-Ganz catheter at autopsy. This device would be considered a combination external and internal medical device.

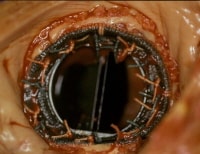

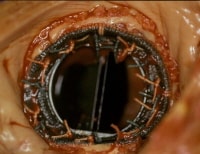

A prosthetic mitral valve in situ at autopsy.

A vena cava "umbrella" device, designed to "catch" large thromboemboli, preventing massive pulmonary embolism in the setting of deep venous thrombosis.

III - Clinical chemistry and clinical toxicology devices

A vast majority of these devices can be considered "laboratory" devices, including test systems and laboratory instruments. As such, most of these devices do not come into direct contact with patients, so they are unlikely to be involved in any death.

These devices belong mostly to class I and class II. Examples include glucose measurement devices, sodium and other electrolyte measurement devices, laboratory instruments such as mass spectrometers, and various specific toxicology test kits.

IV - Dental devices

Examples of class I devices include intraoral x-ray film holders, temporary crowns, root canal posts, dental drills, injection needles, orthodontic appliances and accessories, and dental floss. Type II dental devices include certain dental cements, ultrasonic scalers, amalgam fillings, various resins, and permanent crowns (porcelain). Examples of class III devices include certain types of bone graft material and mandibular condyle prostheses.

V - Ear, nose, and throat devices

Almost all ear, nose, and throat devices are classified as class I or II devices. Examples of class I devices include air-conduction hearing aids, otoscopes, nasopharyngeal catheters, and various hand-held surgical instruments.

Examples of class II devices include bone-conduction hearing aids, tympanostomy tubes, and bronchoscopes. The rare class III ear, nose, and throat devices include the suction antichoke device and the tongs antichoke device (instruments used for emergent removal of objects obstructing the airway).

VI - Gastroenterology and urology devices

As with the ear, nose, and throat devices, most gastrointestinal and urology devices are classified as class I or II devices.

Class I devices include items such as manual surgical instruments, enema kits, and ostomy pouches. Examples of class II devices include endoscopes, lithotriptors, urologic catheters, peritoneal dialysis systems, and gastrointestinal tubes (such as nasogastric tubes and feeding tubes). Class III devices include items such as inflatable penile implants and implanted blood access devices (vascular shunts for hemodialysis).

An example of a feeding tube.

VII - General and plastic surgery devices

Included within this medical panel of devices are various commonly used general medical products, such as gloves and dressing materials, as well as many specific surgical devices.

Examples of class I devices include removable skin staples, surgical gloves, gauze dressings, manual surgical instruments, and tourniquets. Examples of class II devices include implantable staples, absorbable sutures, surgical drapes, surgical clips, skin adhesive, surgical mesh, facial plastic surgery prostheses (eg, nose, ear, chin), and extremity splints. Class III devices include items such as absorbable powder for use on surgical gloves, absorbable hemostatic agents, tissue adhesive, and breast implants.

VIII - General hospital and personal use devices

This is another category that is primarily composed of class I and II devices. Examples of class I devices include patient scales (for weighing a patient), elastic bandages, manual adjustable hospital beds, medical adhesive tape, and tongue depressors. Class II examples include thermometers; spinal fluid pressure monitors; intravenous (IV) fluid containers; electric hospital beds; infant radiant warmers; intravascular catheters; neonatal incubators; IV infusion pumps; hypodermic needles; syringes; and percutaneous, implanted, long-term intravascular catheters. The only class III item listed is the chemical cold pack snakebite kit.

An insulin infusion device assembly. The tubing attaches to the pump itself, which is in the carrying case attached to the belt. The tubing is attached to a subcutaneous infusion port on the abdominal wall.

IX - Hematology and pathology devices

As with the clinical chemistry and clinical toxicology devices section above, this section is largely composed of laboratory instruments and tests, as well as devices associated with processing blood and/or tissue samples. Only occasional items have direct contact with patients.

The items in this category are almost exclusively classified as class I or II devices. Examples include various coagulation tests, automated blood cell counters, microscopes, tissue processing instruments, microscope slides, and stains for tissue sections.

X - Immunology and microbiology devices

This panel is similar to the hematology and pathology device panel and the clinical chemistry and clinical toxicology device panel in that the devices are overwhelmingly considered laboratory devices and are highly unlikely to be directly involved with a patient death. The devices are almost exclusively class I or II devices and include numerous devices within several subcategories, including diagnostic devices, microbiology devices, serologic reagents, immunology laboratory equipment and reagents, immunologic test systems, and tumor-associated antigen immunologic test systems.

XI - Neurology devices

There are 3 subcategories within the neurology device panel, including diagnostic devices, surgical devices, and therapeutic devices. Examples of type I neurology devices include electroencephalograph electrodes, esthesiometers, tuning forks, ventricular cannulas (needles), and many manual surgical instruments.

Type II neurology devices include electroencephalographs, intracranial pressure monitor devices, evoked response electrical stimulators, ventricular catheters, aneurysm clip appliers, manual and powered cranial drills, aneurysm clips, central nervous system fluid shunts and components, external functional neuromuscular stimulators, and implanted peripheral nerve stimulators for pain relief.

Examples of type III neurology devices include ocular plethysmographs, rheoencephalographs, intravascular occluding catheters, cranial electrotherapy stimulators, implanted cerebellar stimulators, implanted diaphragmatic/phrenic nerve stimulators, implanted neuromuscular stimulators, and electroconvulsive therapy devices.

An implanted nerve stimulator. Note that the location and appearance of the device in this particular case mimics that of a cardiac pacemaker.

An nerve stimulator after removal at autopsy. Note that the leads remain attached to sections of nerves, which have also been removed.

Metallic devices used to refasten a portion of skull removed during emergency craniotomy.

XII - Obstetric and gynecologic devices

Besides therapeutic, diagnostic, surgical, prosthetic, and monitoring devices, this panel includes another category, assisted-reproduction devices.

Type I devices include fetal stethoscopes, various manual surgical instruments, manual suction breast pumps, and menstrual pads. Examples of type II obstetric and gynecologic devices include colposcopes, laparoscopes, ultrasonic imagers, fetal scalp spiral electrodes, intrauterine pressure monitor devices, fetal vacuum extractors, forceps, contraceptive diaphragms, and tampons. Type III devices include items such as transabdominal amnioscopes, fetal scalp clip electrodes, expandable cervical dilators, and contraceptive intrauterine devices.

XIII - Ophthalmic devices

Included here are numerous diagnostic, therapeutic, prosthetic, and surgical devices.

Examples of class I devices include nonimplanted artificial eyes, manual ophthalmic surgical instruments, various diagnostic devices, and eye shields. Class II devices include ophthalmoscopes, eye sphere implants, ophthalmic lasers, and nonextended-wear contact lenses. Examples of class III ophthalmic devices include intraocular lenses, intraocular pressure measuring devices, intraocular fluids and gases, and extended wear contact lenses.

XIV - Orthopedic devices

Orthopedic devices include many prosthetic and surgical devices, as well as a few diagnostic devices.

Class I orthopedic devices include items such as many manual surgical instruments and many arthroscopic surgical instruments. Examples of class II devices include arthroscopes, intramedullary fixation rods, bone cement, and certain portions of joint prostheses. Class III devices include certain prosthetic joints.

A hip prosthesis removed at autopsy.

XV - Physical medicine devices

Included within this panel are diagnostic, prosthetic, and therapeutic devices.

Examples of type I devices include crutches, arm slings, and mechanical wheelchairs. Examples of type II devices include muscle stimulators, limb prostheses, powered wheelchairs, powered muscle stimulators, and certain ultrasound devices. Type III physical medicine devices include rigid pneumatic structure orthosis devices, stair-climbing wheelchairs, and certain ultrasound devices.

A physical medicine device is depicted in the image below.

Something as relatively "simple" as a mechanical wheelchair may contribute to certain deaths.

XVI - Radiology devices

Medical devices within the radiology panel are primarily for diagnostic or therapeutic use.

Examples of type I devices include nuclear whole body scanners, radiographic film, manual radionuclide applicator systems. Type II radiology devices include magnetic resonance imagers (MRIs), various ultrasound devices, fixed and portable radiograph machines, computed tomography (CT) machines, and radionuclide radiation therapy systems. An example of a type III radiology device is a transilluminator for breast evaluation.Scene Findings

In some cases, it is apparent by scene examination, initial body examination, or by witness statements, that a decedent has an implanted medical device. Depending on the device type, collecting and retaining additional, device-related evidence from the scene may be important for investigators. For example, if a diabetic has an implanted insulin pump (see the following image), collecting all insulin containers, any additional syringes present at the scene, and any logbooks that may be present would be advisable for the investigators.

An insulin infusion device assembly. The tubing attaches to the pump itself, which is in the carrying case attached to the belt. The tubing is attached to a subcutaneous infusion port on the abdominal wall.

In cases in which a sudden death occurs during the performance of a medical procedure, the scene is typically extensively altered by the emergent attempts at resuscitation that follow the initial patient deterioration. These can be some of the most difficult scenes to secure and evaluate. After death has been declared, the medical personnel involved in the event should be advised to not disturb anything. Nothing should be removed from in or on the body. Investigators should arrive as soon as possible and secure the scene. Interviews with all involved persons and bystanders should take place as soon as possible. Investigators should learn as much as possible about the procedure and medical devices used.

Medical devices and records should be secured and retained during the initial scene investigation. Investigators should use common sense when selecting which devices should be secured. For example, if a scenario appears to involve a likely electrocution, securing the sharps disposal container is probably not necessary. However, if the case involves the possibility of inadvertent medication overdosage or administration of the wrong medication, then securing all needles and syringes, including those contained in the sharps disposal container, is most appropriate.Trace Evidence

The implanted medical device itself may contain valuable trace evidence, although not necessarily in the classic sense. For example, if an implanted device is infected and has led to a death related to sepsis, a valuable piece of evidence to collect during autopsy is a microbiologic culture of the device. Investigators and pathologists must have a high index of suspicion regarding the possible mechanism of death and evaluate the scene and body for possible important trace evidence.

When deaths occur in a hospital or other healthcare setting, educating healthcare providers to leave all medical devices in place and undisturbed on or in the body is important.5Gross Examination and Findings

First, in a vast majority of such cases, the implanted medical device has absolutely nothing to do with death. Second, in the rare case in which the device played a role in death, the pathologist, before autopsy, must know as much as possible about the device, the condition for which it is employed, and the possible problems or complications known to occur with the device. This may require interviewing physicians or other healthcare professionals.

Third, in cases in which the device is found to be responsible for death, the pathologist must document all findings by photography (and possibly other means) and retain the device (if possible). Fourth, pathologists should be aware that certain devices may still be functional after death. As such, some may pose a potential safety risk for the pathologist and others. In addition, some devices can be evaluated in order to test their functionality or to provide important data that might assist in the death investigation.

Some other issues of importance should be addressed before autopsy. If the case is a death that occurred during a medical procedure, contacting the hospital risk management department and/or nursing supervisor for assistance may necessary. In all such cases, hospital personnel should be advised to not remove anything from the body. With any device-related death, all medical records should be reviewed and copied. Discussion of the case with the patient's physician and other healthcare staff is advisable, if possible. All conversations should be appropriately documented. Consider collecting blood and other samples from the hospital laboratory if the death occurred in the hospital or shortly after discharge. Attempt to anticipate questions that may be asked by healthcare professionals, family members, and/or attorneys.5

During the autopsy, pathologists should strive to fully document all findings, including the presence and condition of implanted medical devices. Depending on the device, removing it and retaining it may be appropriate. The device may need to be evaluated for proper functioning, etc.

Although the FDA does not necessarily provide an evaluation service, it can frequently assist pathologists in identifying an independent laboratory that can perform such testing. Remember that photography is an important form of documentation, even for negative findings. If a medication error or transfusion reaction is suspected, all IV tubing, IV bags, blood component bags, etc, that are received with the body should be retained.

Depending on the case type, various bodily fluids and/or tissues should be collected and appropriately tested. If death occurred at or near the time of vascular or body-cavity injection, the possibility of an air embolism must be considered. Appropriate dissection techniques should be used to check for air embolism (see Special Dissections, below). Likewise, if a pneumothorax is a consideration, appropriate dissection techniques should be used to check for this complication (see Special Dissections, below).5

At all times, whether before, during, or after the autopsy, pathologists should be thorough, detailed, honest, and unbiased. They should strive to provide timely, accurate, well-documented reports. Depending on the case type (coroner/medical examiner vs hospital), pathologists should provide concise opinions regarding the cause and manner of death. Remember that saying "I don't know," or using words such as "possible" or "probable," is acceptable.

Pathologists should be available to discuss the case with appropriate persons. It is wise for pathologists to avoid offering opinions that are outside their realm of expertise. Clinical questions and standard-of-care issues are best left to appropriate clinical specialists. If a device is found to have caused or contributed to death, notification of the FDA is warranted.5 They can be contacted at 1-888-463-6332, 1-800-638-2041, or 301-796-7100.1 Special Dissections

A risk of introducing air into the vascular system of the patient exists with a variety of therapeutic or diagnostic interventions. This is particularly true when large-caliber blood vessels are cannulated or when large-caliber blood vessels are inadvertently punctured or cut. A small amount of air (a few tiny bubbles) entering the venous circulation is typically of little concern; however, if large amounts enter the venous circulation, the large bolus of air can function as a "vapor lock" within the right side of the heart, creating an obstruction to fluid (blood) flow. Any amount of air within the arterial system can have severe consequences "downstream." This is of particular concern if the brain is the end organ. A shunt, such as exists with a patent foramen ovale, can allow venous air emboli to bypass the lungs and enter the systemic circulation, with equally severe manifestations.

Air embolism can result in sudden cardiorespiratory collapse and death. This should be considered a possibility in any procedural-related sudden death in which air could have entered the blood stream. Air embolism has been described in association with various medical procedures, including but not limited to laparoscopic surgery,6obstetric and gynecologic procedures, and various vascular manipulations. Death related to accidental air embolism due to inadvertent connection of the tubing from an automatic blood pressure cuff inflation device to an IV port (all depicted in the images below) has occurred on more than one occasion.

An automatic blood pressure device (sphygmomanometer). This type of device can be set to intermittently automatically inflate an attached blood pressure cuff and record the blood pressure. The tubing from the device must be attached to tubing connected to a blood pressure cuff.

A photograph showing a blood pressure cuff with attached tubing. Note in the lower left of the photo the connection between the cuff's tubing and the tubing from the automatic blood pressure monitoring device.

A photograph showing the relative size comparisons between the tubing from the automatic blood pressure monitor device (left), the tubing from the blood pressure cuff (right), and a "Hep-Lock" intravenous device (top). Because of previous accidental deaths from air embolism when the blood pressure device tubing was inadvertently connected to the Hep-Lock, engineering changes have been made so that the inadvertent connection is theoretically no longer possible.

If an air embolism is suspected, pathologists should first order postmortem chest radiographs. Oftentimes, an area of radiolucency within the right side of the heart is evidence of a large air embolism, as depicted in the image below.

Postmortem chest radiograph showing a radiolucent area within the right atrium (arrows), indicating the presence of an air embolism.

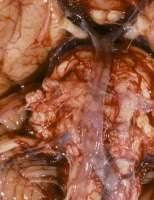

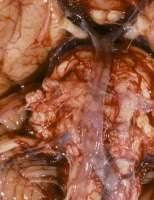

If central nervous system air embolism is suspected, careful examination of the brain should be performed before the remainder of the autopsy. The cutting and removal of the skull should be performed very carefully to avoid introducing artifactual air into the meningeal vessels. Careful inspection of vessels will allow for visual identification of air bubbles, as depicted in the image below.

Intravascular air bubbles within the basilar artery at the base of the brain, from a case of air embolism.

In order to check for an intracardiac air embolism, the best method is to cut a "window" out of the anterior chest wall/plate, over the location of the heart. The opening should be about 4-5 × 4-5 inches; it is very important to avoid cutting any vessels near the sternoclavicular junction. Once the window of chest wall is removed, the anterior pericardium should be opened to visualize the heart.

At this point, if air embolism has occurred, actually visualizing small air bubbles within the superficial vasculature of the heart may be possible. After looking for evidence of air embolism in the epicardial vessels, the heart sac should be filled with water so that the entire heart is under water. Next, a scalpel or needle should be inserted into the right atrium. If air is present, it will escape as air bubbles into the water. Use of an inverted, water-filled graduated cylinder can allow the pathologist to "catch" the bubbles in order to obtain an accurate measurement of the air embolus. The image below depicts a check for air embolism at autopsy.

Checking for an intracardiac air embolism at autopsy.

Pneumothorax

Various procedures can result in the formation of a pneumothorax (or a combined pneumohemothorax). The most typical scenario occurs when a vascular catheter is inserted into the subclavian vein, and it inadvertently perforates the lung, with resultant escape of air into the pleural cavity. As with suspected air embolism cases, postmortem radiographs may be useful in observing a pneumothorax (or pneumohemothorax).

A pneumothorax appears as a radiolucency within the chest cavity, whereas a hemothorax appears as an opacity within the chest cavity. If a pneumothorax is suspected, the pathologist can reflect the skin and underlying soft tissues of the lateral chest wall further than usual, creating "pockets" on either side of the intact rib cage, which can be subsequently filled with water. Once these pockets are filled with water, the pathologist can create a puncture through a submerged intercostal space and look for escaping air bubbles. An inverted, water-filled graduated cylinder can be used to catch and measure the air. This procedure is depicted in the image below.

Checking for a pneumothorax at autopsy.

Infection

Any implanted medical device is at risk for being a site for potential microbiologic organism colonization. Undetected, these localized infections can lead to widespread infection and possibly even sepsis and death. The clinical presentation of such infections is varied. If investigative information suggests that a decedent with an implanted medical device experienced the signs and symptoms of sepsis before death, pathologists should consider the possibility of performing postmortem blood cultures, specific tissue cultures, and medical device cultures, along with appropriate histologic sampling.7 Special Autopsy Procedures

Anesthesiology

Deaths occurring during anesthesia are more likely to be related to idiosyncratic reactions (sudden cardiovascular collapse during general anesthesia) or other reactions (anaphylaxis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome) to anesthetic drugs, rather than to anesthesia-related medical devices themselves. In any potential drug-related death, evaluating the drug delivery device or system (eg, anesthesia machine, IV tubing, syringe, catheter) may be important. Measuring drug levels within postmortem blood samples or other fluids (cerebrospinal fluid for epidural or spinal anesthesia) may also be warranted.

If anaphylaxis is a possibility, measuring postmortem blood samples for tryptase and possibly antibodies specific to the offending drug may also prove useful. In some cases involving drugs, the problem is not that too much drug was given, but that the drug was delivered to a wrong location (eg, intraspinal rather than epidural space, intravascular instead of subcutaneous).

A common concern at autopsy in cases in which resuscitation was attempted involves the location of the endotracheal tube. When this concern exists, pathologists should check the internal location of the tube. Discovery of an inappropriately placed tube (within the esophagus) may or may not be important regarding the cause of death.

Evaluation of prehospital emergency medical services (EMS) may indicate that no signs of life existed before or during resuscitation attempts. If such is the case, the esophageal intubation likely did not contribute to death. If signs of life existed before the esophageal intubation, an esophageal intubation could be considered a contributing cause of death. Up-to-date technology within EMS protocols, using various gas sensors, makes discovery of and subsequent correction of esophageal intubations more likely during actual resuscitation attempts.

Cardiovascular

One of the most commonly encountered medical device-related deaths involves the perforation of a blood vessel, with subsequent hemorrhage. Often, the hemorrhage is internal and remains undetected clinically until it is too late, or perhaps it is never suspected or detected clinically. Devices causing such perforation may be vascular catheters or introducers, guidewires, or other intravascular devices, such as stents.

Such perforation may be intentional or unintentional. An example of an intentional perforation resulting in death involves perforation of the anterior wall of the femoral artery during cardiac catheterization, with subsequent postprocedure exsanguination. An example of an unintentional perforation involves the placement of a subclavian central catheter, with appropriate perforation of the superficial side of the vessel, but inadvertent perforation of the distal side, with subsequent perforation of the underlying parietal pleural lining and rapid development of a lethal hemothorax. Inadvertent perforation of the heart can result in hemopericardium with cardiac tamponade.8 The images depict a couple of these scenarios.

A hemopericardium as seen at autopsy.

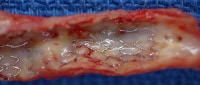

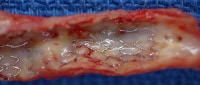

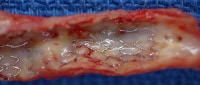

An intravascular stent used in the creation of a portosystemic shunt in the setting of severe cirrhosis. Note the metallic mesh configuration, as well as the relatively sharp ends of the device's wire mesh. These are purposefully designed as sharp ends so that they embed within the surrounding tissue, thus preventing movement of the device after deployment. This particular device actually embolized to the right atrium during deployment, resulting in perforation of the right atrial wall, hemopericardium, cardiac tamponade, and death.

Another cardiovascular device-associated death involves a coronary artery dissection (with or without thrombosis) following angioplasty (with or without stent placement). In these cases, suggesting that an actual error occurred during the procedure is difficult, because the entire purpose of the procedure is to induce a certain amount of trauma (compression/fracture of atherosclerotic plaque in order to enlarge the vascular lumen).

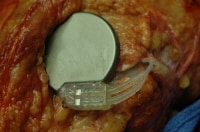

Cardiac pacemakers are typically located in the soft tissues of the upper left chest region. An inexpensive method for determining whether or not the pacemaker is still operational is to remove it and connect the leads to the antenna leads of an FM radio. If the pacemaker is operational, an audible "click" will be heard via the radio speakers. More detailed pacemaker evaluation requires professional assistance.

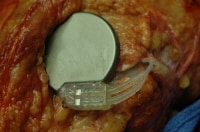

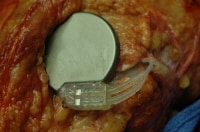

Implanted cardiac defibrillators are located in a similar location as simple pacemakers (see the image below). Care should be taken by pathologists when a device is discovered in this location. Pacemakers are harmless, whereas defibrillators pose a potential safety hazard, as they can discharge. If questions exist regarding the type of device, assume that it is a defibrillator.

The chest of an individual who died from severe underlying heart disease. Note the scar, as well as the elevation of the skin overlying an implanted automatic implanted defibrillator.

Under no circumstances should a defibrillator be manipulated without first ensuring that it is inactivated with a powerful magnet (available via the local cardiac catheterization laboratory or the defibrillator manufacturer) (see the following images).

After initial skin and subcutaneous tissue reflection, the implanted defibrillator remains encased in fibrofatty tissue.

The next step is to use a magnet (present in the specimen bag in the photo) to deactivate the defibrillator. In this photo, the magnet is not yet in position.

In this photo, the magnet is properly positioned over the underlying defibrillator. The defibrillator can now be safely removed.

This is a photograph showing the defibrillator in situ, after removal of the surrounding scar tissue. Because the magnet is no longer attached to the unit, it is potentially active or dangerous as is.

A photograph showing a defibrillator with intact leads. Again, in this photo, without the magnet attached to the unit, it is wise to consider the unit potentially active and/or dangerous. Once removed, the dry device should be placed into a sealed specimen bag.

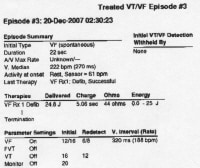

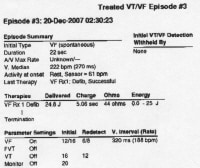

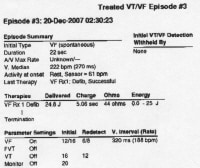

Manufacturer representatives can also electronically interrogate the device after removal to provide potentially useful information, including a timeline that may allow a relatively accurate determination of the time of death, as shown in the images below.9

A device used by manufacturer representatives to interrogate an implantable cardiac defibrillator removed at autopsy.

A manufacturer representative can often electronically interrogate the defibrillator and provide the pathologist with data concerning the device's activity. This photo shows part of a printout of such data. This information may prove useful in the death investigation.

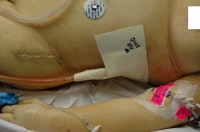

Occasionally, more complex cardiac devices are encountered at autopsy, such as a totally artificial heart or an ventricular assist device (see the images below). With these, the pathologist should work closely with the cardiothoracic surgeon to fully understand the potential issues of concern. Pathologists should perform dissections carefully to identify any anastomosis complications. Oftentimes, the surgeons, hospital where the surgery was performed, and/or manufacturer will request that the device be removed and sent to them for evaluation.

An autopsy photograph of an elderly woman with an implanted ventricular assist device. The tubing is exiting the upper right abdominal wall.

The appearance of a ventricular assist device after initial opening of the body and chest plate removal.

During removal of this ventricular assist device at autopsy, the anterior aspect of the heart is dissected in situ, in order to show that the device is properly positioned and attached.

A photograph showing a ventricular assist device after removal from the body at autopsy.

Ear, nose, and throat

Perhaps the most common and serious device-associated complications related to otorhinolaryngology surgery are vascular/hemorrhagic concerns, similar to surgical intervention elsewhere. However, particularly when internal nasal surgery is concerned, remember that the base of the skull (which can be relatively thin in places) is in close proximity to the nasal passages and sinuses. As such, disruption of the bone can lead to potentially lethal brain and/or cerebral vascular trauma.10

Gastroenterology and urology

Various lethal complications may be associated with gastrointestinal or urologic medical devices. None is particularly common. Vascular perforation, often inadvertent, can lead to exsanguination and death. Rupture of a viscus can lead to peritonitis with subsequent sepsis and death. Urosepsis from various causes, some related to trauma, some related to obstruction, can likewise lead to sepsis and death.

A case of air embolism during lithotripsy has been described in which a suction device was improperly connected such that air was forced into the body.11 Various lethal complications have been described in relation to indwelling feeding tubes. The most common complication described is aspiration pneumonia, but other complications can also occur, including leakage with peritonitis and malnourishment.12 At autopsy, pathologists need to ensure the proper location of feeding tubes (see the following images).

An example of a feeding tube.

A photograph at autopsy showing that a gastric tube is in proper position.

General and plastic surgery

Deaths related to device-related complications in general and plastic surgery are numerous and varied. Any surgical intervention is potentially complicated by vascular disruption and subsequent exsanguination. Procedure-related and/or device-related infection is another potentially lethal complication. Examples include postoperative peritonitis and subsequent sepsis related to a retained surgical sponge. Disruption of a suture, a staple, or a surgical clip can lead to exsanguination, ruptured viscus, or other lethal outcome.

In the 1980s and 1990s, numerous reports suggested an association between breast implants and various connective tissue diseases. Numerous cohort studies have since concluded that no evidence exists of an association between breast implants and any traditionally recognized connective tissue disease, includingsystemic sclerosis, fibromyalgia, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren syndrome. Others have contended that an as-of-yet undefined or "atypical" connective tissue diseaselike condition is associated with breast implants; however, most recent investigations fail to confirm such an association.13

The following is an image of breast implants removed at autopsy.

Two breast implants removed at autopsy. The one on the left was perforated by the same trauma that resulted in the woman's death.

Neurology

Neurologic devices can include those used to deliver medication into or around the spinal canal. If a death is suspected of being related to inappropriate location of the device's catheter or inappropriate dosage of medication, careful autopsy dissection to document the exact location of the catheter tip is extremely important. Collection of various tissue and fluid samples for subsequent toxicology samples may be in order. If the delivery device is electronic, evaluation of its function may be required.

Obstetric and gynecologic

Complications related to obstetric and gynecologic medical devices are varied, with many being similar to those occurring with other surgical disciplines. Uterine perforation related to an indwelling device, or from surgical instrumentation, can lead to hemorrhagic or infectious complications.

Orthopedic

Implanted orthopedic prosthetic devices are extremely common. Because so many artificial joints exist, occasional lethal complications associated with them should not be surprising. As with any type of surgery, postoperative complications such as deep venous thrombosis, with subsequent pulmonary thromboembolism, may occur following orthopedic surgery. This particular complication may actually be more common in the typical population undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery. The older age of the patients, coupled with the inflammation and postoperative changes associated with lower extremity surgery, add to the already elevated risk for developing deep venous thrombosis that exists in postoperative patients.

A rare complication that occurs in elderly patients undergoing hip replacement surgery is manifest as sudden cardiorespiratory collapse (usually resulting in death), typically occurring during or shortly after application of bone cement. The exact mechanism of the sudden death is not well understood. It is generally not believed to be related to fat embolism, although this rare complication is another possible lethal outcome related to orthopedic surgery.14

In both of the preceding examples, evaluation of the surgery site at autopsy is usually unremarkable other than normal operative changes. Depending on the case, the pathologist would be wise to at least open the surgical site to look for any evidence of abnormality or complication, such as infection or marked hemorrhage.

A knee replacement prosthesis in situ at autopsy, after removal of the surgical staples and exposure of the joint space. Depending on the case, documenting the presence of the device and the condition of the surrounding tissues may or may not be important.

Special Handling

A coronary artery stent as visualized at autopsy.

A vena cava "umbrella" device, designed to "catch" large thromboemboli, preventing massive pulmonary embolism in the setting of deep venous thrombosis.

An intravascular stent used in the creation of a portosystemic shunt in the setting of severe cirrhosis. Note the metallic mesh configuration, as well as the relatively sharp ends of the device's wire mesh. These are purposefully designed as sharp ends so that they embed within the surrounding tissue, thus preventing movement of the device after deployment. This particular device actually embolized to the right atrium during deployment, resulting in perforation of the right atrial wall, hemopericardium, cardiac tamponade, and death.

Another potential hazard involves implanted electrical devices. This is particularly worrisome with automated defibrillators, as they can discharge. Theoretically, protective rubber gloves provide some degree of protection; however, disabling the defibrillators before handling them is best. A strong magnet can be obtained from the manufacturer representative or from any local cardiac catheterization laboratory. Placing the magnet against the device should disable it (see the images below). The magnet should be kept in place during and after removal, until the dried device (with dry, intact leads) can be safely placed into a biohazard bag or container. Note that automatic defibrillators may be evaluated (electronically interrogated) by the manufacturer representative to provide potentially useful information for death investigation.9

The next step is to use a magnet (present in the specimen bag in the photo) to deactivate the defibrillator. In this photo, the magnet is not yet in position.

In this photo, the magnet is properly positioned over the underlying defibrillator. The defibrillator can now be safely removed.

This is a photograph showing the defibrillator in situ, after removal of the surrounding scar tissue. Because the magnet is no longer attached to the unit, it is potentially active or dangerous as is.

A photograph showing a defibrillator with intact leads. Again, in this photo, without the magnet attached to the unit, it is wise to consider the unit potentially active and/or dangerous. Once removed, the dry device should be placed into a sealed specimen bag.

A device used by manufacturer representatives to interrogate an implantable cardiac defibrillator removed at autopsy.

A manufacturer representative can often electronically interrogate the defibrillator and provide the pathologist with data concerning the device's activity. This photo shows part of a printout of such data. This information may prove useful in the death investigation.

Other implanted electrical devices, such as nerve stimulators, may also have potential risks for pathologists and others (see the following images). Contacting the manufacturer representative before autopsy in order to evaluate the potential risk is the best course of action.

An implanted nerve stimulator. Note that the location and appearance of the device in this particular case mimics that of a cardiac pacemaker.

An nerve stimulator after removal at autopsy. Note that the leads remain attached to sections of nerves, which have also been removed.

Histology and Microscopic Examination and Findings

Examination of tissues which surround and abut an implanted medical device typically reveal chronic inflammatory changes, which may include foreign body giant cells, other chronic inflammatory cells, and fibrosis (scarring). Under most circumstances, these changes should be considered normal. Unless the inflammatory reaction has progressed to the extent that actual tissue integrity is compromised, resulting in hemorrhage or another catastrophic outcome, such inflammatory changes should probably not be implicated as causing or contributing to death.

In many other cases in which an implanted medical device is implicated in death, in which the tissues surrounding the device have no discernible gross abnormality, histologic sections of tissues near the device are probably not necessary. However, it is wise for pathologists to perform routine histology on other organs and tissues to document and confirm various natural disease processes, which may or may not play contributory roles in death.Photography and Documentation

When a device has, in fact, caused or contributed to death, photographically documenting the autopsy findings is also prudent. In some instances, depending on the mechanism of death, adequately photographing the findings may be difficult; however, if possible, such photographs will be valuable documentation (proof) of the final autopsy findings and opinions.

Depending on the implanted device, additional methods of documentation are available. With some devices, actual removal and retention of the device is possible. If the pathologist elects to remove the device, removal must be done in a way that does not damage the device. The device should be retained in a manner that reduces or eliminates the risk of subsequent body fluid contamination. With some devices, keeping the device in a sealed, labeled container of formalin is reasonable. For others, a Ziplock specimen bag is more appropriate. The device should be photographed in situ and again after being removed. The container should be appropriately labeled.

Some implanted electronic devices may be interrogated electronically by manufacturer representatives in order to gain valuable information regarding the functioning of the device, or perhaps what was happening physiologically with the patient before death. The most common example of this situation involves the implantable automated cardiac defibrillator, in which interrogation of the device allows one to determine if and when the patient experienced an arrhythmia and whether or not the device discharged in response to arrhythmia.Ancillary and Adjunctive Studies

Diagnostic Criteria

Providing in-depth discussion of cause and manner of death issues is beyond the scope of this article; however, a brief review will be provided. No universally accepted protocol regarding how a medical device (or other intervention) should be included in a cause of death ruling exists. One proposed classification scheme attempts to classify suspected therapy-related deaths into 5 possible categories. After performing the autopsy, the pathologist attempts to determine the extent of contribution the particular medical therapy had in causing the death of the patient. The 5 options are as follows10 :

The determination of manner of death is another major challenge for pathologists investigating a death that is suspected of being related to medical therapy. In cases that are classified as class I or class II deaths in the above classification scheme, a "natural" manner of death is logical.

Class III cases are not only equivocal regarding cause of death, but also with regard to manner of death; however, one could reasonably argue that, because the therapy contributes significantly to death, the manner of death should not be simply natural. The usual manner in such cases is "accident" (although rare jurisdictions within the United States have "therapeutic complication" as a choice regarding manner of death). Great debate exists with these types of cases, and the final manner-of-death ruling often depends on the type of intervention, the specific mechanism by which it contributes to death, and sometimes even by convention. Ruling the manner of death "accident" is more acceptable for class IV deaths, and the ruling is usually obvious and without debate in class V deaths.8,9

Another proposed algorithm for manner of death determination in cases suspected of being related to medical therapy is as follows. If the stress of a medical intervention contributes to death, but no other complication exists, then the manner should be "natural." If a complication that is related to the medical therapy exists, but it is appropriately implemented therapy, and the complication is considered common, inherent, or chronic, or the complication is related to a nonacute, nontraumatic, natural physiologic response to therapy, then the manner should be "natural."

If the medical therapy involves a true mistake or error, then the manner should be "accident." If the therapeutic complication results in unintended traumatic injury that causes or contributes to death, the manner should be "accident." If the death results from mechanical failure of a medical device, the manner should be "accident." If the death is related to unanticipated reactions to drugs or other substances, the manner should be "accident."8,9

If a case is being performed as a hospital autopsy, and the manner of death, as described above, suggests that the case is best ruled as an "accident," then the pathologist should refer the case to the coroner or medical examiner (even if the autopsy is already complete).Common Misconceptions

The second misconception regarding implanted medical devices is that if a device is actually found to be responsible for death, then it is generally assumed that the device was defective. Although a defective device is certainly a possibility, the reality is that, in most instances, a properly functioning device was used improperly, or the implantation procedure itself somehow resulted in inadvertent injury, or underlying natural disease (or sometimes natural bodily function) or tissue reaction to the device resulted in dislodgement or ineffective function of the device. In these instances, the device itself is not defective.Issues Arising in Court

Because the FDA regulations are intended to protect patients from unintended harmful consequences of medical devices, examples of truly defective devices are relatively rare. More common are cases where a properly functioning device is used improperly, or the implantation procedure has complications that lead to death, or underlying diseases and tissue reactions with the device lead to untoward effects and death. These types of cases are also likely to result in civil court proceedings.

Perhaps the most important point for pathologists faced with the examination of a death that is suspected of being related to an implanted medical device is to be as unbiased as possible when performing the autopsy and review. Document the facts and findings of the case. If, in the opinion of the pathologist, the device contributed to death, then the pathologist should be able to provide a well-reasoned explanation as to how, from a pathophysiologic standpoint, death occurred and was related to the device.

Having well-documented autopsy findings is important. Cases that ultimately go to court often take years to work their way through the system. For this reason, pathologists should ensure that their autopsy reports (and notes, if retained) are accurate, appropriately detailed, and easily understood, such that review of them several years later will provide enough useful information for testimony. The use of photography can be a very useful method of documenting certain device-related deaths.Multimedia

Media file 1: This autopsy photo shows several medical devices, many of which are combination internal/external devices, including an arterial line, an intravenous line, and a chest tube. Also note the recent surgical scar, containing implanted (totally internal) sutures, as well as the electrocardiograph (ECG) pad, a totally external device.

Media file 2: An autopsy photograph showing multiple medical devices, including a tracheostomy tube, which would be classified as an anesthesiology device.

Media file 3: Implanted vascular graft material used to replace an area of ascending aortic aneurysm and dissection.

Media file 4: A coronary artery stent as visualized at autopsy.

Media file 5: A photograph of a Swan-Ganz catheter at autopsy. This device would be considered a combination external and internal medical device.

Media file 6: A prosthetic mitral valve in situ at autopsy.

Media file 7: A vena cava "umbrella" device, designed to "catch" large thromboemboli, preventing massive pulmonary embolism in the setting of deep venous thrombosis.

Media file 8: An example of a feeding tube.

Media file 9: An insulin infusion device assembly. The tubing attaches to the pump itself, which is in the carrying case attached to the belt. The tubing is attached to a subcutaneous infusion port on the abdominal wall.

Media file 10: An implanted nerve stimulator. Note that the location and appearance of the device in this particular case mimics that of a cardiac pacemaker.

Media file 11: An nerve stimulator after removal at autopsy. Note that the leads remain attached to sections of nerves, which have also been removed.

Media file 12: Metallic devices used to refasten a portion of skull removed during emergency craniotomy.

Media file 13: A hip prosthesis removed at autopsy.

Media file 14: Something as relatively "simple" as a mechanical wheelchair may contribute to certain deaths.

Media file 15: An automatic blood pressure device (sphygmomanometer). This type of device can be set to intermittently automatically inflate an attached blood pressure cuff and record the blood pressure. The tubing from the device must be attached to tubing connected to a blood pressure cuff.

Media file 16: A photograph showing a blood pressure cuff with attached tubing. Note in the lower left of the photo the connection between the cuff's tubing and the tubing from the automatic blood pressure monitoring device.

Media file 17: A photograph showing the relative size comparisons between the tubing from the automatic blood pressure monitor device (left), the tubing from the blood pressure cuff (right), and a "Hep-Lock" intravenous device (top). Because of previous accidental deaths from air embolism when the blood pressure device tubing was inadvertently connected to the Hep-Lock, engineering changes have been made so that the inadvertent connection is theoretically no longer possible.

Media file 18: Postmortem chest radiograph showing a radiolucent area within the right atrium (arrows), indicating the presence of an air embolism.

Media file 19: Intravascular air bubbles within the basilar artery at the base of the brain, from a case of air embolism.

Media file 20: Checking for an intracardiac air embolism at autopsy.

Media file 21: Checking for a pneumothorax at autopsy.

Media file 22: A hemopericardium as seen at autopsy.

Media file 23: An intravascular stent used in the creation of a portosystemic shunt in the setting of severe cirrhosis. Note the metallic mesh configuration, as well as the relatively sharp ends of the device's wire mesh. These are purposefully designed as sharp ends so that they embed within the surrounding tissue, thus preventing movement of the device after deployment. This particular device actually embolized to the right atrium during deployment, resulting in perforation of the right atrial wall, hemopericardium, cardiac tamponade, and death.

Media file 24: The chest of an individual who died from severe underlying heart disease. Note the scar, as well as the elevation of the skin overlying an implanted automatic implanted defibrillator.

Media file 25: After initial skin and subcutaneous tissue reflection, the implanted defibrillator remains encased in fibrofatty tissue.

Media file 26: The next step is to use a magnet (present in the specimen bag in the photo) to deactivate the defibrillator. In this photo, the magnet is not yet in position.

Media file 27: In this photo, the magnet is properly positioned over the underlying defibrillator. The defibrillator can now be safely removed.

Media file 28: This is a photograph showing the defibrillator in situ, after removal of the surrounding scar tissue. Because the magnet is no longer attached to the unit, it is potentially active or dangerous as is.

Media file 29: A photograph showing a defibrillator with intact leads. Again, in this photo, without the magnet attached to the unit, it is wise to consider the unit potentially active and/or dangerous. Once removed, the dry device should be placed into a sealed specimen bag.

Media file 30: A device used by manufacturer representatives to interrogate an implantable cardiac defibrillator removed at autopsy.

Media file 31: A manufacturer representative can often electronically interrogate the defibrillator and provide the pathologist with data concerning the device's activity. This photo shows part of a printout of such data. This information may prove useful in the death investigation.

Media file 32: An autopsy photograph of an elderly woman with an implanted ventricular assist device. The tubing is exiting the upper right abdominal wall.

Media file 33: The appearance of a ventricular assist device after initial opening of the body and chest plate removal.

Media file 34: During removal of this ventricular assist device at autopsy, the anterior aspect of the heart is dissected in situ, in order to show that the device is properly positioned and attached.

Media file 35: A photograph showing a ventricular assist device after removal from the body at autopsy.

Media file 36: A photograph at autopsy showing that a gastric tube is in proper position.

Media file 37: Two breast implants removed at autopsy. The one on the leftwas perforated by the same trauma that resulted in the woman's death.

Sunday, October 17, 2010

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

(Enlarge Image)

Labels: Implanted Medical Devices

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment